The Disconnect

November 18, 2020

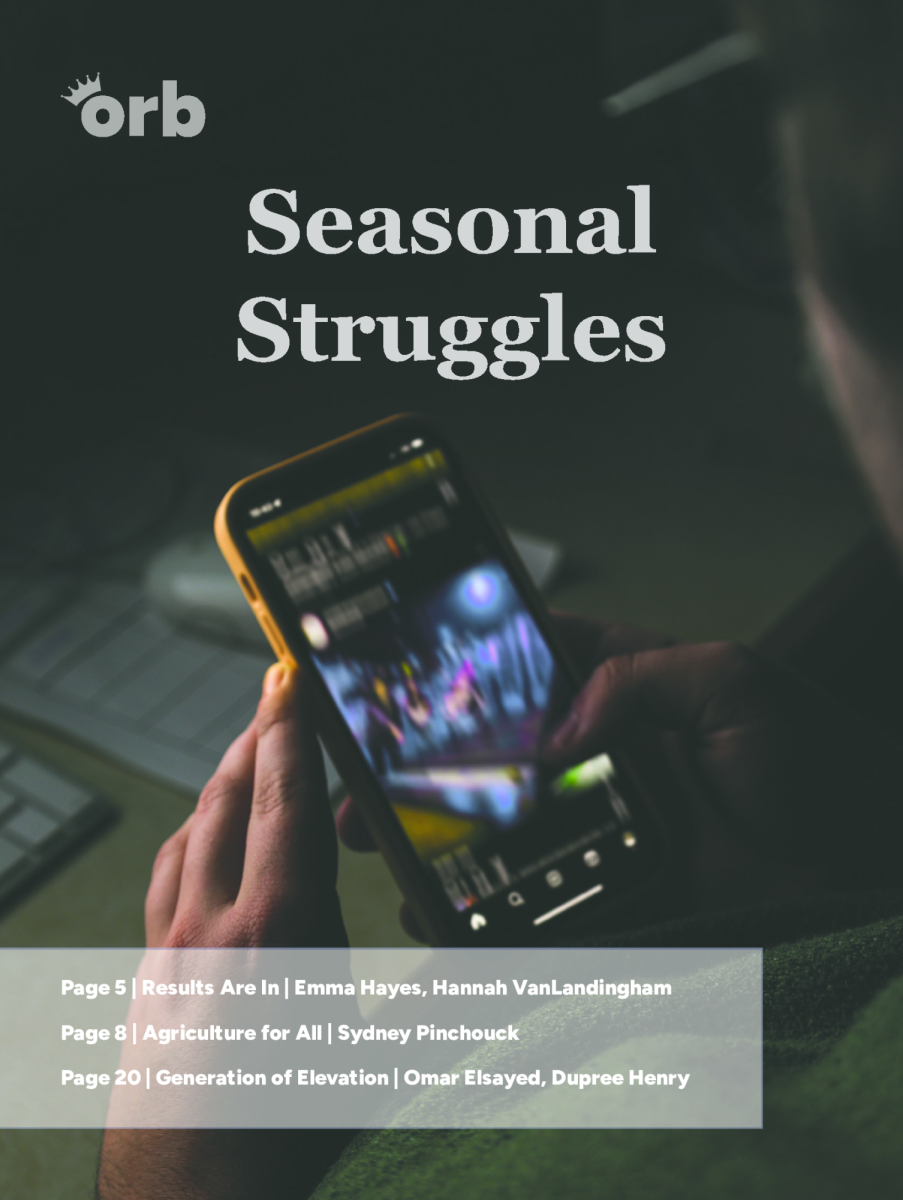

For many of us, handheld technology has become an engraved portion of our daily lives, with endless scrolling and typing dominating any given moment during a day. This reliance on technology may be detrimental, although, if not managed properly and intentionally.

According to The Washington Post, teenagers spend an average of 7 hours and 44 minutes on their phones per day, which solidifies technology as an integral part of a student’s daily life.

This begs the question:

Why are teenagers, and everyone else, so addicted to their phones?

To find the answer to this question, a look into the brain’s reward center is necessary. When we open up a social media app or our message screen, each notification brings us a small hit of dopamine, which is a chemical released throughout the brain commonly referred to as the “pleasure chemical”.

First, we must look at the reward center in the human brain, which releases dopamine when any “feel-good” activity is completed. These activities include things like engaging in social interaction, eating food and pretty much any activity that the brain deems helpful towards our survival. These activities like communication are hardwired into our brains as necessities, starting with humans in the Neolithic era who had evolved to communicate and find food. As a result, the human brain rewards these activities with the release of dopamine.

The social interaction segment of this reward center, however, has basically been hijacked by the social media companies, who format their apps to trick the brain into believing that it is engaging in social interaction. This is achieved by the big, flashy notifications and the bright colors used to represent a like or follow request on these apps. Resulting from this, social media likes and notifications constantly cause our brains to respond with unhealthily large frequency of dopamine releases. Additionally, the brain’s reward center recognizes a pattern of where it can receive this gratification, which causes people to constantly return to social media in order to feel that gratification again and again.

Because of this, those of us who frequently use social media are subject to a form of addiction, with our brain’s reward centers always reminding us of where we can find instant gratification, where we would feel happy and absolved of stress. Many problems arise with this, however.

For example, this reliance on technology and social media for our sense of feeling good forces us to completely move past the slow-paced or sometimes boring parts of life. This may seem beneficial, as being bored obviously isn’t very fun, but it’s quite necessary to tolerate boredom if one is to do hard things in life.

For instance, imagine standing in a line with rows of people ahead of you, with no end in sight and nothing to look at or hold your attention, like a phone. In this time, the brain learns how to tolerate boredom, which is an obstacle necessary for important tasks like: doing homework, writing an essay, getting through a boring part of a movie, listening to a class, having a long conversation and so much more. Without a willingness to tolerate the unexciting aspects of life, we have no way of enjoying the worth-while parts of the human experience that may not be as flashy or intriguing as the instant gratification of a like button.

Some might counter the argument against social media with the point that scrolling through one of these apps “Makes me feel good, so I do it” or “What’s wrong with having a good time online?”

This raises the question: What is the problem with feeling good all of the time? Isn’t that a good thing?

In theory, yes, if there were to be a guaranteed way of maintaining a good feeling, it would be completely illogical to refrain from engaging in it, but this situation is completely different. Once a shot of dopamine is released, the feel-good effects soon wear off, causing the person affected to feel less happy in contrast. This feeling of unhappiness causes the brain’s reward center to relaunch the search for gratification, which it knows can be found when returning to a social media page. This is where the similarities to drug addictions arise with the use of technology, where normal life becomes less gratifying than the continual shots of dopamine guaranteed by these short term “feel-good” activities. So, really, the constant return to the endless scrolling online proves to make us more dopamine-shocked and unhappy, which is the harsh reality of our culture’s reliance on short-term gratification with technology.

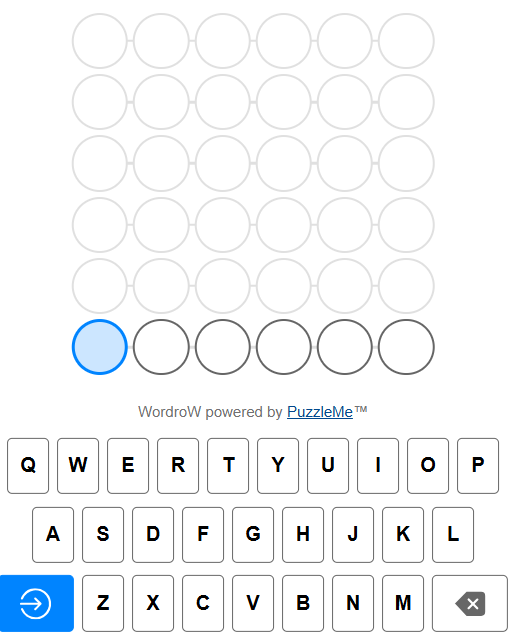

So, suppose you wanted to reduce your reliance on technology; How would one go about it?

First, a self-analysis is key to realizing how much social media actually dominates your life. To find out, try this simple test:

Step 1. Sit down in a room with no distractions or stimulus, just yourself and the room. Leave your phone in a completely separate room.

Step 2. Sit there for 10 minutes and do absolutely nothing. During that time, count how many times you feel the urge to go online or go grab your phone from another room. The results may surprise you.

After assessing how prevalent technology may be in your life, start with a “digital detox”, which is a slot of time in which you dedicate to removing technology from all aspects of your life. An adventurous person might spend a whole day offline, which seems like an eternity in today’s age. As a start, try refraining from social media, or even technology altogether for as long as you feel is necessary to really break the habit of relying on instant gratification.

Finally, is the time for a compromise. Of course, living a life completely without social media could harm us, with the potential loss of contact with friends who communicate exclusively on those apps. The key is finding a middle ground, a place where you can still enjoy the benefits of social media without developing a heavy reliance on its potentially addictive tendencies. If we are all able to achieve this middle-ground, wherever that may be, our experience with technology and the world around us can become a much more positive one.